INFODAD.COM: Family-Focused Reviews

(++++) BRAHMS AND BEYOND

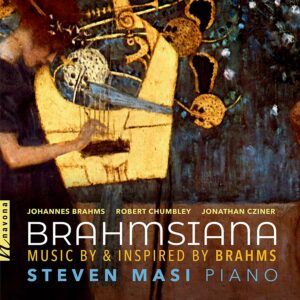

Brahms’ own later pieces, however, often have a succinctness that in no way reduces their communicative potential. In particular, his final four works for solo piano, Opp. 116-119, are intimate, personal, nostalgic, mostly quiet, and very much unlike his earlier, expansive, virtuosic and large-scale piano music. Pianist Steven Masi uses this fact to excellent effect on a new Navona CD on which he plays Brahms’ Op. 117 and Op. 118 – plus two contemporary pieces that are responses to and commentaries upon Brahms’ music. This could easily degenerate into an exchange of consonance for dissonance, a set of variations unrecognizable in their relationship to Brahms’ original material, or some other form of “tribute” that would be self-aggrandizing and would not elucidate anything. But that is not what happens here, thanks to the genuineness of Robert Chumbley’s and Jonathan Cziner’s respect for Brahms and for what Masi is trying to do (Cziner’s work was actually commissioned by Masi). First, Masi plays the Three Intermezzi, Op. 117, sensitively and pensively, bringing forth their rather resigned and elegiac elements – ones that are usually described in Brahms as “autumnal,” an overused adjective that actually fits this music well. “Crepuscular” and “nocturnal” are other apt descriptions of these three works, especially in the sensitive way in which Masi handles them. He follows them with Chumbley’s Brahmsiana II, itself a set of three intermezzos – which contain no quotations at all from Brahms’ Op. 117 but are directly inspired by it in their mood, overall feeling, and most of their pacing. They do look beyond Brahms harmonically, but they are not filled with dissonance for its own sake, and in fact Chumbley shows himself determined to maintain Brahms’ essential lyricism while bringing his musical language into the present day. After this work, Masi plays Brahms’ Op. 118, which includes four intermezzi, a ballade and a romance, and which alternates in mood between intensity and deep resignation – these pieces were dedicated to Clara Schumann, whom Brahms obviously adored for decades but who only respected him. Although the overall mood of the six pieces, taken as a totality, is somewhat lighter than the mood of the three works in Op. 117, the final piece in Op. 118 is genuinely tragic in feeing and leaves a lasting impression of almost unbearable sadness. Masi is at his best here, capturing the multiplicity of moods of the whole set of six pieces while dwelling to just the right degree on the emotional depth of the last one. Cziner’s Echoes of Youth follows this, and while the juxtaposition is a trifle awkward – it is hard for anything to follow Op. 118, No. 6 – Cziner is as attuned to Brahms’ feelings and musical approaches in his way as Chumbley is in his. Cziner offers four pieces, including two intermezzi, a romance and a ballade – and intriguingly gives the intermezzi titles that are well-known to Brahmsians: Frei Aber Einsam, “free but lonely,” which violinist Joseph Joachim considered his personal motto, and Frei Aber Froh, “free but joyful,” which was Brahms’ counter to his friend’s downbeat statement. Yet Cziner uses the Joachim motto for the second intermezzo, which is the last of the four pieces, and that fact, along with the character of the music, results in a final feeling of reflective melancholy that fits very well indeed with the deeper and more troubling impression left at the end of Brahms’ Op. 118. Cziner, like Chumbley, does not hesitate to use more-modern compositional materials than Brahms employed, but here too they are employed judiciously and never simply for effect. What Chumbley and Cziner do here, led and abetted by Masi, is to have a kind of pianistic conversation with late-in-life Brahms, empathizing with him while showing that his feelings, thoughts and music remain quite relevant to musicians and audiences in the 21st century. That is a very impressive accomplishment for everyone involved: Masi, Chumbley, Cziner, and Brahms himself.

Brahms’ own later pieces, however, often have a succinctness that in no way reduces their communicative potential. In particular, his final four works for solo piano, Opp. 116-119, are intimate, personal, nostalgic, mostly quiet, and very much unlike his earlier, expansive, virtuosic and large-scale piano music. Pianist Steven Masi uses this fact to excellent effect on a new Navona CD on which he plays Brahms’ Op. 117 and Op. 118 – plus two contemporary pieces that are responses to and commentaries upon Brahms’ music. This could easily degenerate into an exchange of consonance for dissonance, a set of variations unrecognizable in their relationship to Brahms’ original material, or some other form of “tribute” that would be self-aggrandizing and would not elucidate anything. But that is not what happens here, thanks to the genuineness of Robert Chumbley’s and Jonathan Cziner’s respect for Brahms and for what Masi is trying to do (Cziner’s work was actually commissioned by Masi). First, Masi plays the Three Intermezzi, Op. 117, sensitively and pensively, bringing forth their rather resigned and elegiac elements – ones that are usually described in Brahms as “autumnal,” an overused adjective that actually fits this music well. “Crepuscular” and “nocturnal” are other apt descriptions of these three works, especially in the sensitive way in which Masi handles them. He follows them with Chumbley’s Brahmsiana II, itself a set of three intermezzos – which contain no quotations at all from Brahms’ Op. 117 but are directly inspired by it in their mood, overall feeling, and most of their pacing. They do look beyond Brahms harmonically, but they are not filled with dissonance for its own sake, and in fact Chumbley shows himself determined to maintain Brahms’ essential lyricism while bringing his musical language into the present day. After this work, Masi plays Brahms’ Op. 118, which includes four intermezzi, a ballade and a romance, and which alternates in mood between intensity and deep resignation – these pieces were dedicated to Clara Schumann, whom Brahms obviously adored for decades but who only respected him. Although the overall mood of the six pieces, taken as a totality, is somewhat lighter than the mood of the three works in Op. 117, the final piece in Op. 118 is genuinely tragic in feeing and leaves a lasting impression of almost unbearable sadness. Masi is at his best here, capturing the multiplicity of moods of the whole set of six pieces while dwelling to just the right degree on the emotional depth of the last one. Cziner’s Echoes of Youth follows this, and while the juxtaposition is a trifle awkward – it is hard for anything to follow Op. 118, No. 6 – Cziner is as attuned to Brahms’ feelings and musical approaches in his way as Chumbley is in his. Cziner offers four pieces, including two intermezzi, a romance and a ballade – and intriguingly gives the intermezzi titles that are well-known to Brahmsians: Frei Aber Einsam, “free but lonely,” which violinist Joseph Joachim considered his personal motto, and Frei Aber Froh, “free but joyful,” which was Brahms’ counter to his friend’s downbeat statement. Yet Cziner uses the Joachim motto for the second intermezzo, which is the last of the four pieces, and that fact, along with the character of the music, results in a final feeling of reflective melancholy that fits very well indeed with the deeper and more troubling impression left at the end of Brahms’ Op. 118. Cziner, like Chumbley, does not hesitate to use more-modern compositional materials than Brahms employed, but here too they are employed judiciously and never simply for effect. What Chumbley and Cziner do here, led and abetted by Masi, is to have a kind of pianistic conversation with late-in-life Brahms, empathizing with him while showing that his feelings, thoughts and music remain quite relevant to musicians and audiences in the 21st century. That is a very impressive accomplishment for everyone involved: Masi, Chumbley, Cziner, and Brahms himself.